The pelvis provides stability to the spine and counterweight to the cranium. Pelvis provides movement in the hip sockets, tailbone, and pelvic floor. This allows muscular and neuro vascular flow between the legs, trunk, and cranium. It is thereby unblocking the rigidity and congestion in the pelvis. Hence, it is important to align and balance the pelvis.

Evolutionarily, standing upright on two legs is a remarkable phenomenon. Bipedalism is something we take for granted, yet standing presents its own challenges. Structurally, movement is easier, and more efficient on four legs rather than two. This is due to the way the forces are distributed between pelvic and shoulder girdles in the four-legged posture. Thus, it is easier for coyotes, reindeer, and pumas to maintain a balanced spine.

While standing on two legs, our center of gravity is props upward, far from the ground. As a result, kinetic forces (motion) typically become bottled up in the hip joint. In yoga, hip openers that involve external rotation serve to stretch and strengthen the fan-shaped muscles, that radiate out along the outer hip. The task of loosening constriction in the hip region is the most painstaking (and painful!) part of the yoga practice.

Architecture of the pelvis

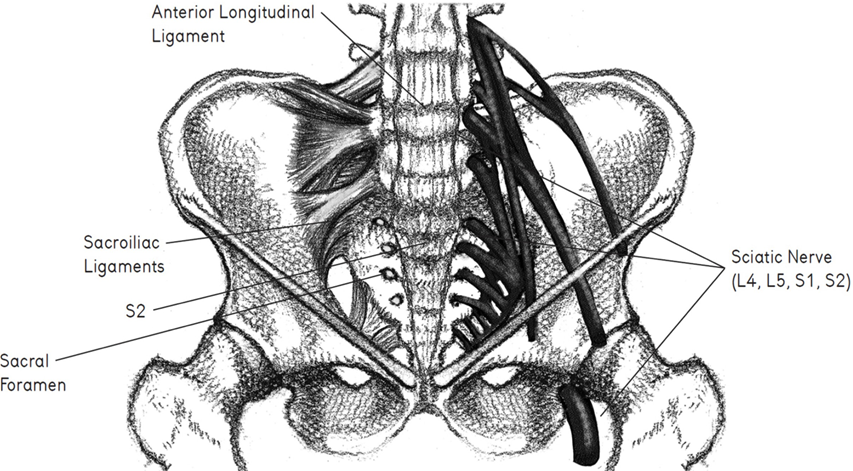

The ilia or iliac bone resembles wing like structure that spread and create a protective sphere. This provides a sanctuary for housing pelvic organs with vessels, nerves that transit from the abdomen to the legs.

The curved edges of the upper ilia have multiple attachment sites for muscles. Some sweep down from the abdomen and some muscles climb upward from the sides of the legs. The curve of each ilium enables a broad range of motion in the leg, hip socket, and side waist.

The design of the uppermost femur is unique to bipeds. Because the thighbone achieves virtually a right angle at its proximal end, where it angles into the hip socket. This is the neck of the femur.

If the hip joints are mobile, the essential fluids (blood, lymph, & cerebrospinal fluid) pass without any restriction through the pelvis. In turn, it affects the flow deep within the spine. This flow of essential fluids was thought to be a source of both longevity and immortality. When the ball of the femur in the hip joint swivels and turns, it helps propel the life-sustaining inner fluids.

The hip joint is often a zone of significant compression and tension. The entire complex of the hip and buttock muscles is frequently tighter on one side causing asymmetry. The hip sockets may assume different characteristics, or personalities, right to left. This could be due to trauma, genetics, repetitive strain, short-legged syndrome, or postural traits. Thereby, one leg assumes the burden of weight more than the other. In light of chronic asymmetrical holding, one hip may slip, shear, or catch.

When the hip joints are uneven, it is comparable to an automobile with poor alignment. This can cause the entire physical structure to veer or pull to one side. Repeated pulling to one side can aggravate the ligaments and labrum in one or both hip sockets. If chronic displacement causes painful restriction in the area of ligament and around the hip socket, then the individual may be a candidate for hip replacement.

Watch this video to align your body correctly to in Tadasana.

Stabilizing the Hip

Most students find it hard to practice certain asanas on one side in comparison to the other.

Sometimes imbalance is due to gluing in the Myofascia around the hip, and sometimes it is due to excess laxity. A joint with too much play or mobility can be as problematic as a restricted one. Especially in the hip, given the load-bearing demand on the hip sockets.

To stabilize and secure the ball and socket complex of the hip, we need to anchor the head of the femur firmly. Standing asanas like Trikoṇāsana, Pārśvakoṇāsana , and Vīrabhadrāsana A and B help to generate bilateral symmetry in the hip sockets. One-legged balancing asanas such as Vṛikṣāsana and Ardha Chandrāsana are especially helpful in aligning and building sturdiness in the weight-bearing hip joint. This securing of the femoral heads generates stability for the entire pelvis and spine. Bearing weight through the bones aids in building greater bone density and increases absorption of calcium into the bones.

Physiologically, the marrow of the long bones of the femurs & the marrow of the ilia are critical production sites for red blood cells. In both Āyurveda and Chinese medicine, bone marrow is equated with the body’s quintessential life spirit.

Inner channels: Nadi’s of the leg

Inner rivers of blood, lymph, and nerve emerge from deep within the abdomen. It courses alongside the navel, and dive downward through the interior pelvis. The iliac nerve, artery, and vein are carefully cached and protected by the walls of the ilia; they are lifelines, transporting nerve signals and blood to the leg. Exiting the pelvis, they transit through the upper groins, and tunnel down the inside channel of the leg as the femoral arteries, veins, and nerves.

Yoga asanas such as Ardha Chandrāsana serve to open these conduits. Effectively modifying blood pressure, heart rate, the circulation of lymph, respiratory rhythms, and consciousness. To open the myofascial compartment of the inner thigh is to open the core sheath of the body. This serves to improve the flow of blood and nerve impulses that travel between the hip and leg.

Asanas that passively restore the inner leg, such as Supta Baddha Koṇāsana, Supta Pādāṅguṣṭāsana, etc are therapeutic. They open the Nāḍīs that transit down the inner thigh. They also increase the circulation of blood and lymph. This improves neurological flow through the pelvis, down the leg, and into the foot.

The Heels of the Pelvis

The dynamic and curved wings of the ilia attach to the underlying pelvic bones are ischia. The sitting bones are knobby protrusions, and their thick and bony mass adds weight and stability to the pelvis. They are important guides for determining how to bear weight in seated poses. The heel of the foot supports the weight of the leg. Similarly, the heel of the sitting bone supports the weight of the spine & pelvis. Both are spherical, heavy, and rigid. They both make contact with a supporting surface. The heels to the floor in standing, the sitting bones to the cushion or mat when seated.

It is important to observe how the sitting bones make contact with the floor. If one side of the pelvis bears more weight when sitting, then the entire pelvis & spine may pitch to the side. It is common when sitting at work or eating dinner for the body weight to routinely teeter to one side. Chronic displacement to one side can cause compression in the hip. In turn foreshorten the lower back, and possibly contribute to scoliotic curvature of the spine.

How weight is borne by the sitting bones plays a role in determining the alignment of the spine, shoulders, and skull. It is key to visualize Samasthiti Tadasana in the sitting bones. In turn generate equal balance on both sides of the pelvis. The seated asanas, Daṇḍāsana is the samasthiti, as it helps to orient and balance the two sides of the body.

Pelvic Diaphragm and Respiratory Diaphragm

A succession of horizontally oriented diaphragms partition and support various regions within the body. Each diaphragm can distend downward, contract inward, lift upward, and expand laterally. The plantar fascia, the thick fibrous webbing on the sole of the foot, is the first diaphragm; the pelvic diaphragm is the second. The pelvic floor is a perforated yet resilient muscular sling at the base of the pelvic cavity. Multiple slips of muscle comprise the sling, banded together in order to provide support for the pelvic.

Mūla Bandha

The pelvic floor has the capacity to alternately widen and narrow, then retract and drop. It is important to remember that there is myofascial continuity between the muscles of the legs and the pelvic floor when learning mūla bandha. All too often the perineum is a receptacle for strain and can become a storehouse for repressed tension. When the body and mind are under threat and there is acute fear, the soft tissues of the perineum clamp in defense. This is particularly true in light of any trauma or violation in and around the pelvis.

Combined postural and psychological pressure also build up in the hip joints, buttocks, low back, hamstrings, and groin. The flight-or-fight response typically shows up as constriction in the prime movers—the legs. Yet given that the perineum is supple and impressionable, it is susceptible to strain and distress.

One of the primary aims of practicing yoga is to encourage blood flow into the hips and pelvis. Alternately saturating, flushing, and rinsing the structures within the pelvic bowl and lower spine. Proper circulation of fluids into the organs and glands combined with good neurological function can help regulate hormonal activity. One of the primary effects of a hip opener is vasodilation. It allows blood, lymph, and cellular fluid to bathe and nourish the tissues. Yoga asanas together with the lift of mūlā bandha help change the pressure dynamics in and around the pelvic floor. Thereby monitoring neurological and circulatory rhythms within the pelvic cavity. For example, in Vinyāsa yoga practice, the perineum alternately expands and narrows. In the course of the sun salutation when doing Urdhva Mukha Svānāsana, the pelvic floor retracts. Conversely, in Adho Mukha Svānāsana the pelvic floor releases and widens.

The Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor

The perineum is shaped like a diamond, with the anterior triangle housing the genitalia, and the posterior triangle surrounding the anus. The anterior perineum is yin (ligaments, tendons & fascia), for it contains the reproductive organs. The back portion is yang (muscles), for it includes the base of the digestive tract, the root of the colon, and the anus. Each of these triangular muscular webbings can be engaged in isolation. A pulse of movement, a vibratory quiver, felt in the anterior triangle and specifically in the central tendon between the two triangles, is the essence of mūla bandha.

Activating the bundle of muscle at the posterior triangle (including the anal sphincter muscles) is more available to voluntary control. Gripping the tailbone portion of the perineum is called Ashvinī Mudrā and includes contraction of the cylindrical rings around the anus. Contracting and alternately expanding the anterior triangle is linked to the subtle body due to its effects on reproductive vitality and ojas, the body’s most refined tissue.

Ojas refers to semen in the male body and the ovum in the female body, and their cyclical movements that are governed by hormonal rhythms within the brain. For men, anatomically controlling the anterior perineal triangle is linked to ejaculation control. This is an ability that is regarded in both Taoist and yoga practices to be the key to overall vitality. By yoking the anterior perineum, the pranic sheath within the body (prāṇa-maya- kośa) expands and is fortified. Control of the perineum is valuable generally, because as people age, the contractile capacity of the urethra wanes and both men and women suffer from incontinence. Mūla bandha helps maintain the sphincter control necessary for timed urination.

Pregnancy and the Pelvic Floor

The perineum is vulnerable to prolapse, due to the weight of collapsing organs, as a result of forced defecation, or from trauma during labor. During vaginal birth, descending pressures from the fetal cranium against the pelvic floor may cause the perineum to overstretch, tear, and lose contractile capacity. Following birth, the pelvic floor and the uterus may prolapse. This is due to the rigors and strain involved with downward abdominal force and laxity within the core structures of the pelvis and abdomen. During delivery, an episiotomy can also compromise the pelvic floor, leading to scar tissue and abnormal pulling within the musculature of the pelvic diaphragm.

A postnatal yoga practice helps to generate greater structural integrity to the pelvic diaphragm, as well as in the inner groins, hip rotator muscles, and abdomen. To prevent or minimize the likelihood of postpartum prolapse, women are advised to wait until the pelvic organs have returned to their pre-pregnancy size before returning to active practice. This can take up to two months after delivery. A protocol for postnatal yoga includes the harmonious coordination of mūla bandha and uḍḍīyāna bandha.

Getting to the Root

In many regards, the discipline of yoga involves getting to the root. We have established how the base of the spine and pelvic floor serve as roots for the entire body. It brings about balance & stability. Thus the root support (mūlādhāra) is the origin of the chakra system relating to the body’s innermost biological rhythms.

This blog was originally written by Eric Angus, Level 2 Indea Yoga Teacher, and edited by Team Indea Yoga. This was a part of his dissertation work during her Level 2 Teacher Training Course.